- Home

- Melanie Little

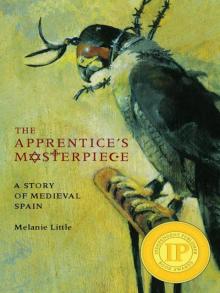

The Apprentice's Masterpiece Page 3

The Apprentice's Masterpiece Read online

Page 3

He was strangled before he was burned—

out of mercy. In the end, he’d repented.

But his eyes remained open.

We stood and watched.

When the flames reached his head,

you couldn’t see much.

His hair, catching fire, haloed smoke.

Yet after a while I did notice something

dropping to the ground.

We were far back in that crowd.

By decree, the whole of Cordoba was there

to witness the spectacle.

In the dreams, though, the eyeball returns in

horrid detail.

It’s as close as a pea might be,

on my plate.

Little Lies

When I wake from these dreams

I am sweating and shouting.

Mama hears and comes in.

She is angry, I know.

Not with me. At the fact

we’re all made to watch

these foul shows.

Yet she consoles me.

We even try

to make it a joke.

“Did you see the eyeball?” she’ll ask me.

“Was it red and bloodshot from his drinking

too much for his last hurrah?”

Once or twice I have woken in tears, like a child.

Mama tells me, those times, that I’m safe.

We’re all safe.

Everything will be fine.

She knows I don’t really believe it.

Neither does she.

But there’s something amazing

about those bland words.

Those little lies that claim

our lives are normal.

To say them, to hear them,

feels gutsy. It’s as close

to rebellion, maybe,

we will ever come.

Parchment

Now Yuce Tinto is gone!

No one has seen him

for one month at least.

Not even in church.

He is the man

who sells us our parchment.

He has a kind heart.

His prices are always

too cheap by half.

Papa sends me. Yuce

has no wife. Maybe he’s ill,

helpless in his bed.

No one’s there.

His home’s been ransacked.

Shreds of parchment and paper

lie strewn like plucked feathers

all over the floor.

Everything points to the Inquisition.

Yuce, too, is a converso.

And I once heard him say

that Jews and Muslims can

go to heaven, if they are good people.

Who knows to whom else

he’s said such rash things?

Poor Yuce.

He had a big mouth—

and many friends.

Both spell danger.

But together…

Mama cries when she hears it.

“What will become of that poor,

gentle man?”

I’m selfish. Our one source for parchment

has just disappeared.

Without it, we can’t do our work.

So it’s like we’ve no food.

What will become, my poor, gentle Mama,

of us?

Collecting

First, it was dead butterflies.

For a while, Roman coins

I’d find in the earth.

But this type of collection?

It doesn’t suit me.

At long last, I can roam

through these streets. Yet I’d rather

be home in my room.

No one likes to pay debts.

Not even clients who once mussed my hair

and brought me sweet treats.

They make promises.

(Those come cheap.)

One gives me a barren old hen

in exchange for a prayer book

that took eight days to copy.

I pass by the mansion

of Don Barico.

He owes nothing.

In fact, he always pays in advance.

Often he’ll even add wonderful gifts.

Plump partridge pies.

Candied almonds. Soft leather covers

for books.

I sigh. The word candied haunts me

all the way to our door.

Gift

I’m scarcely inside

when I hear a knock.

There stands Don Barico himself,

as if he’s been conjured

by my wishful thoughts.

But what twisted magic is this?

There’s no partridge pie in his arms.

Instead, at his side, stands a boy.

Well, I think he’s a boy.

There’s a thin line of hair

just above his top lip.

(There’s more above mine.)

But the rest of him—lost

in a mountain of cloth.

His robes touch the ground,

hiding even his shoes.

His hair in his turban could be

long or short or painted magenta,

for all I can see it.

There are two things, though,

you can’t miss.

On his robe, just below his right shoulder,

the red patch of the Moors.

Above it, on his cheek, a black S.

Inked or burned, I can’t tell,

right into his nut-colored skin.

Don Barico hasn’t brought us a present.

He’s brought us a slave.

Monkeys

I love Mama’s laugh.

And God knows, it’s a rare enough creature

these days.

But this time, it’s wrong.

“Look at them stare at each other,” she says.

“Like two nervous monkeys

peering over their barrels!”

No, I was just looking, not staring.

He’s the one who won’t quit.

Like I’m the strange one.

The stranger.

We Are Four

Never mind what we’ll do with a fourth mouth to feed

when there’s barely enough for ourselves.

What will we do with two more working hands?

No commissions, no parchment,

not even much ink.

Plus, he’s another

person to fear.

I’ve heard of some slaves, malcontents,

behaving like spies.

One insult from their masters:

they run to the Office.

They tell the first tale, no matter how false,

to enter their minds.

Papa, it’s true, is a master scribe.

As am I, for that matter.

Most masters have servants.

Who cares?

We’ve always done fine

on our own, thank you kindly.

Papa’s no fool. It won’t be a day

before he sends this Moor back.

Arabic

“Amir is still learning

his Spanish, Ramon. You

must help him.”

“Yes, Papa.”

Ha.

My friends and I talk

about him

even though

he’s right here.

Like speaking aloud

with a donkey around.

He looks at us, straight.

Sometimes he blinks

like a fly’s flown too close.

But even could he decode

what we say, well,

aren’t his ears

tucked too tight

in that turban of his?

Shoo

Mama and Amir

now rule the kitchen.

I brood by the hearth—

it’s just me sitt

ing here, so it hasn’t

been lit—and try not to listen.

Even with Mama,

he doesn’t say much.

But she doesn’t give up.

She babbles on, drowning

his silence with streams

of her talk.

When Papa or I try to help

with the meals, she just shoos us.

We are clueless and clumsy.

But Amir can do things.

Well, wait till I tell

the boys in the quarter

he can cook like a girl!

Strut

Amir drops

the docility act

when we’re out of doors.

Everyone knows he’s our slave:

I’ve told them.

But he struts like an equal.

He holds his head high.

They all can see it.

This kid, Paco, said,

“He makes like he

is the master of you!”

Companion

One thing I’ll say:

with Amir here, Mama and Papa

don’t nag me as much about going out.

I know why. They think I can’t

get into trouble

with him as their spy.

What do they fear? That I’ll scale

the high wall of a convent

if I’m left alone?

We’re sent to the market;

I choose a route so roundabout

I feel dizzy. (If I’m stuck

with this guy, I vow to have fun.)

Amir narrows his eyes

but says nothing.

What can he say?

The streets wind like serpents.

For some reason I think of

a story I know, of Hercules.

As an infant, he cast

a swarm of snakes from his cradle.

He must have owned slaves.

Did he permit them to walk

by his side, as I do?

Retort

We turn from some alley

(I admit it: we’re lost)

right into their midst.

A long line of men in fine robes.

On their shoulders, a dais.

There, clad in silk, sits a tall Virgin Mary

just as if she were real, and a queen.

The men seem to glow in their pride.

Women stand alongside,

throwing petals of roses at the men’s feet.

From a high window nearby

someone wails, “Nuestra Señora!”

Our beloved lady!

The voice is so full

of both sorrow and joy

it prickles my neck.

Then, out the side of one eye,

I see a swoop of cloth.

It’s Amir, down on his belly,

lips to the ground.

This has been law since the Christians

won Cordoba back from the Moors.

All Muslims must prostrate themselves

when an image of Mary or Christ

proceeds past.

Amir stands.

He catches me staring.

“You kneel in your church,

do you not?” he asks.

His Spanish—I gawk—

is smooth as glass.

Questions

So it seems that Amir’s understood

every word that I’ve said.

He tries not to smile

as I come to grips with his trick.

But there’s the smallest of smirks,

like the spout of his mouth

has a minuscule crack.

Now, at the market,

he speaks to the merchants,

asking for this many olives (only a few)

or that much salt. (I can’t say

I mind this: I hate to shop.)

But on the walk home

we say not a peep.

Of what could we speak?

What I most want to ask

I know I should not.

Why’s he a slave? Did he steal something?

Kill?

Has he ever been sold

in a market himself?

How many times

has his back felt a whip?

Does a person—kind of like cramps

in your hands when you write—

get used to it?

Do slaves dread tomorrows?

Plan escape? Dream of death?

I make it a game. Imagine I’ll ask him

whatever I want (though I won’t).

By the time we are home

I’ve chosen two.

What do you hope for?

That’s one. And the second:

what do you fear?

If I were a slave,

I think I’d fear nothing.

Sure, I would dread

every lash of the whip.

But dread and fear

are not the same thing.

What’s there to fear

when you have nothing left?

Pupil

After supper, the roles

are reversed.

I help Mama clean up,

like a servant.

I guess washing dishes is easy enough—

even for blockheads like me.

Papa and Amir sit out

by the fire.

(Yes, for him, it is lit!)

They scribble away

on two separate slates.

(Amir’s got an old one

of mine. No, no one’s asked

if I’d mind.)

What do they write?

What else but Arabic?

You see, our Moorish slave

is teaching Papa—master scribe—

how to write!

Mama must see me scowling.

“Try to be gracious,” she scolds.

“He may be a slave,

but Señor Barico brought him here

for a reason. He was meant

as a gift to Papa.

A great one.”

I nod, say good night.

(Is that gracious enough?)

But I think: Mama has lost

all her fine talent

for comforting me!

Pity

Can it get any worse?

Now I’m pitied

by our slave!

“My language is so difficult.”

He wears a kind smile.

“Many great men do not know it.”

I see. He thinks I think less

of Papa for this.

But that’s not the problem.

No one’s thought to teach me Arabic.

So I think less of myself.

Can you blame me?

The Kingdom barely knows I exist.

And now I’m old rags

here in my own house.

Ache

And why Arabic?

What makes it

such a great gift?

Hebrew—though it might

get us arrested—

that I could see

Papa wanting to learn.

Hebrew is tied to us,

to who we are.

Is Papa so quick

to forget this?

Listen to them!

They’re at it again.

Studying, reading.

Talking language stew.

Mama waits up, dozing

by the fire.

I retire, but I hear them.

Their sound makes a lump

down deep in my belly.

It feels like I’ve wolfed a whole bushel

of berries, rotten and soft.

Mark of the Slave

When Amir and Papa finish at last

with their work for the night,

Amir comes to sleep in my room.

Aren’t slaves meant to sleep

on the staircase or something?

It’s not that

he snores.

In fact, he’s too quiet.

And that thing on his face

gives me nightmares.

Night after night,

he lies the same way.

On his left side.

Cheek against sky.

So unless the night’s shade

is blacker than pitch,

I can see that S.

It shines up from his face

like some dark star.

What manner of man

burned that mark?

A Christian? A Jew?

A slave-trading Moor?

Does it matter?

Most nights, the S is the last

thing I see before my eyes close.

And the first thing I see upon waking—

whether or not

I’ve opened my eyes.

Al-Burak

Amir and I walk to the well

at the end of our street.

A voice from the grate

of a high dark window.

“Hey!”

I look up. The sun blinds my eyes.

“Fly away, al-Burak!”

Should I defend him?

Is a master dishonored

by taunts to a slave?

A rock falls near my foot.

And a second.

Amir’s far ahead.

The rocks, and the name, are for me.

It rankles.

We conversos are as used to rude names

as an ass is to slaps.

Marrano. Turncoat.

Jewish wolf in sheep’s skin.

Al-Burak—that’s—a new one.

I can’t help it.

I like to know what I’m called.

It sounds Arabic. I’ll ask Amir.

No, I won’t.

A man in the market

called him damned shit-skinned cur.

He’d laugh to know I was irked

by this one little slur.

Proud

We don’t speak a word

on the way home.

I try to act calm, but I’m not.

Water sloshes and jumps

from my pail like the drops are at sea

and abandoning ship.

The black cloud’s above me

all through dinner.

Everyone’s quiet.

It’s clear they can see it.

“You’re a fool,” Amir says

as he helps clear the plates.

“Don’t you know al-Burak

was a magical steed?

“It carried my prophet, Muhammad,

on its back up to heaven.

I myself would be proud

to be called such a thing.”

That figures.

Amir is just proud to be—

well, Amir.

That’s the difference, I guess,

between him and me.

But how can I be proud?

The Apprentice's Masterpiece

The Apprentice's Masterpiece